Review

All lectures are freely available on this site.

The New Physics – its encounter with religion and God

بسم الله الرحمن الرحيم وصلى الله على سيدنا محمد وعلى ءاله وصحبه أجمعين وسلّم

Title: The New Physics – its encounter with religion and God

Author: Abdassamad Clarke

Publication date: 16/3/2013

Assalamu alaykum. Welcome to the Civilisation and Society Programme of the MFAS. This is the seventh of 12 sessions which make up the Technique and Science module. The lecture will last approximately 40 minutes during which time you should make a written note of any questions that may occur to you for clarification after the lecture.

7. The New Physics - its encounter with religion and God

Heisenberg said, “In his earlier physics, Einstein could always set out from the idea of an objective world subsisting in space and time, which we, as physicists, observe only from the outside, as it were. The laws of nature determine its course. In quantum theory this idealization was no longer possible.”

We can only talk about a physics whose heydays began in 1900 as ‘New’ because we are largely still grappling with its meanings, and have failed to go beyond them. Those intense decades saw result after result spilling out, results which were grouped in two rough categories: the very large and the very small, the cosmic and the sub-atomic. After Planck, Einstein’s pivotal early work lay at the root of all the subsequent development but his most famous work was the large-scale theories on relativity whereas Niels Bohr, Heisenberg, Pauli, Dirac and Schrödinger along with a large number of others were working in the sub-atomic realm. A great deal of work has gone into trying to reconcile the very different implications and contradictions of these two approaches. So we have an initial bursting out of absolutely astonishing results and since then we have had an attempt at consolidation and at coming to terms with them, but sometimes an earnest struggle to restore the old understandings even if in the guise of the new physics.

It is well to bear in mind three things: first, that science is in Heidegger’s words the ‘theory of the real’ – in other words this is a deeply philosophical indeed metaphysical and often religious issue; second, the bifurcation that is marked by Goethe’s work when the science we know today went off into the increasingly abstract, mathematical speculative sort which articulates a theory ‘about the phenomenon’ in our modern sense and Goethe’s reminder that ‘the phenomenon is the theory’. We saw how Heisenberg, although very aware of and sensitive to Goethe’s reasoning, nevertheless stood staunchly by the abstract mathematical approach.

The epoch that precedes our story is dominated by the metaphor of the machine. The solar system is a giant machine. Living beings are ultimately machines. The cosmos is a machine. Man is the only exception because of his ‘rational soul’ but of course belief in God and in man’s soul is under threat. The whole scheme is summed up in one word: ‘determinism’. If one only knew the initial conditions of any system, including the entire cosmos, and the different laws governing all the processes, one should in principle be able to calculate and predict any subsequent state at any moment. It is this philosophy that Einstein, in spite of his work lying at the base of the quantum discoveries, was to struggle to restore until his dying day.

For the purposes of our lecture, I will concentrate on one specific aspect: the relationship of the scientists themselves to religion and next week in the lecture on The New Weapon, we will look at the important relationship to power.

I will approach the relationship between science and religion from a number of perspectives: first, the religious backgrounds of the different men and women; second, their own interpretations of their results in a religious sense, whether that was atheistic or theistic.

In talking about Secular Discourse in lecture No.2 “The Rise of Science” we saw the evolution of the new language of humanism, of which science is an essential component, as a kind of safe zone common to people from, first, Catholic and Protestant backgrounds, and then later including Jews. Because it must omit those things that each party would find objectionable in the others’ positions, the language of humanism must necessarily be a lowest common denominator and yet it too is an aspirant to the role of being a religion.

Lastly, there is, given the collapse of theology or at the least its restriction to clerics, the presence of philosophy and metaphysics and what background the different actors in our drama would have had in it.

The results of that astonishing epoch in the early twentieth century are too well known to bear repeating in great detail and so we will summarise them here.

Rather than a continuous spread, light energy was discovered by Planck in 1900 to come in discrete minute quantum packages. He could not make the jump to seeing these packages as corpuscles or particles. It was Einstein in his astonishing series of papers in 1905 who first articulated many of the themes which the next decades would see elaborated, refined and stated in a more finished mode. Niels Bohr, who had worked with Rutherford and J.J. Thomson, made the first quantum model of the atom in which electrons sat in discrete shells and moved without a smooth transition between the different shells. This already defied any kind of physical understandings that people had: where were the electrons when they moved between the shells? The theory did not allow for any in-between. This is the famous ‘quantum jump’.

At first it was the photon – light – which was discovered to be both a particle and a wave, but soon it was shown that the electron and then all particles have equivalent energies and wave patterns.

Einstein showed that mass itself and energy are equivalent to each other and linked by an equation that is perhaps the most famous in science. He also showed that rather than things subsisting and events taking place within space and time, by the hypothesis of the invariable nature of the speed of light, space and time could be seen not as the absolute frame within which things happen but as an expanding and shrinking part of the event and of the things themselves. At great speeds, the sequence of events could be experienced differently by different observers. Not only is time a relative experience but mass and space also. He took the leap of positing that the speed of light is always the same with respect to all parties to an experiment, no matter how fast and in what direction with respect to the light they are travelling. This postulate, as counter intuitive as it is, was to lead to results that are born out by experiment and observation.

Thus, the three absolutes – mass, length and time – upon which classical physics had rested were no longer as absolute a set of reference points. And yet, to all intents and purposes, physics continued on as if they are, since these effects are only observed at speeds close to the speed of light. However, for other purposes Newtonian mechanics is seen to be a good enough approximation. This fudge, however, avoids neatly the very real intellectual transformation that had taken place and allows us to remain in the old worldview while dealing with genuinely challenging discoveries.

For their part, the quantum theorists found, to their utter astonishment, that if the experiment is set up to observe particle behaviour, that is what will be observed, but that if it is set up to observe wave behaviour that is what will be seen. Not only does that mean that matter itself is both particles and waves, but that what one observes depends on what one sets out to observe. This is the famous result that calls into question the very separation between subject and object, observer and observed.

The quantum results were also expressed as probabilities. Thus, neither are we talking about particles nor waves but about the probability that the electron or any other particle might exist in a certain space. Einstein, in spite of the fact that his early paper on photo-electrics had given the impetus to everything that was to follow, refused to accept much of quantum theory and continued to do so until his death. He particularly disliked the introduction of probability theory and said, “God doesn't play dice with the world,” to which Bohr is said to have replied, “Stop telling God what to do with his dice.”

Heisenberg framed his famous uncertainty relation that stated that if you know the velocity of a particle to some degree of precision you know less about its location, and vice versa. They were dealing with the fact that the means by which they observed, the photons of light, were of the same order of magnitude as the objects they observed and thus inevitably affected the process. They came to understand that the nature of what they were working with could simply not be visualised although it could be expressed mathematically.

Early scientists, as we saw in previous lectures, had largely been within the Christian tradition, although since orthodoxy itself was such a disputed issue, their sometimes heterodox positions must be seen in that context. We saw that modern science and scientists emerged during the Reformation when theological disputes rent the fabric of Christendom in a most divisive way that amounted to civil war. Although the Laplacian school is by no means absolutely representative of all scientists, there were nevertheless along with him a substantial body of thinkers who ‘had no need of that hypothesis’ i.e. God. Thus we arrive at the quantum discoveries and relativity with the issue still far from settled and scientists as a body discussing it, and individual scientists writing essays about it.

If being unacquainted with philosophy can be an issue with scientists, their lack of clarity about religion is sometimes overwhelmingly plain to see. For many of our main thinkers, religion is merely the zone of ethics. Thus Heisenberg when asked, in a discussion with Pauli, Dirac, Bohr and others about science and religion, about Planck’s religiosity, said:

"I assume…that Planck considers religion and science compatible because, in his view, they refer to quite distinct facets of reality. Science deals with the objective, material world. It invites us to make accurate statements about objective reality and to grasp its interconnections. Religion, on the other hand, deals with the world of values. It considers what ought to be or what we ought to do, not what is. In science we are concerned to discover what is true or false; in religion with what is good or evil, noble or base. Science is the basis of technology, religion the basis of ethics.”1

This uncharacteristically square and unperceptive remark from Heisenberg reflects accurately the perspective of many of the participants in this 5th Solvay Conference of 1927. It was probably Heisenberg’s attempt to bridge the gulf that separated him and others from Dirac who was a firebrand of a very particularly English sort, who said:

“Paul Dirac had joined us in the meantime. He [Paul Dirac] had only just turned twenty-five, and had little time for tolerance. ‘I don't know why we are talking about religion,’ he objected. ‘If we are honest—and scientists have to be—we must admit that religion is a jumble of false assertions, with no basis in reality. The very idea of God is a product of the human imagination. It is quite understandable why primitive people, who were so much more exposed to the overpowering forces of nature than we are today, should have personified these forces in fear and trembling. But nowadays, when we understand so many natural processes, we have no need for such solutions. I can't for the life of me see how the postulate of an Almighty God helps us in any way.’”2

Pauli, who had sat quietly throughout the discussion was asked his point of view and said: "Well, our friend Dirac, too, has a religion, and its guiding principle is: 'There is no God and Dirac is His prophet.'" We all laughed, including Dirac, and this brought our evening in the hotel lounge to a close.”3

Thus on our spectrum of the quantum physicists, Dirac’s is the bluntest statement of the atheism which is by no means the rule among them. However, this spectrum cannot be understood without grasping the collapse of Judaeo-Christian culture which they were living through because of the bankruptcy of the religious order. These people are post-Christian and post-Jewish and looking earnestly in most cases for some light. Some sought it in past philosophers but many were exploring the nature of matter itself for clues.

Given that people were still emerging from particular traditions, our scientists’ backgrounds are relevant. Some were from Catholic, Protestant and Jewish backgrounds and various combinations of them. Each background undoubtedly coloured their perspectives. Then they adopted a variety of stances.

The man who launched quantum theory in 1900, Max Planck was a deeply religious man. He said:

“As a man who has devoted his whole life to the most clear headed science, to the study of matter, I can tell you as a result of my research about atoms this much: There is no matter as such. All matter originates and exists only by virtue of a force which brings the particle of an atom to vibration and holds this most minute solar system of the atom together. We must assume behind this force the existence of a conscious and intelligent mind. This mind is the matrix of all matter.”4

Bohr was from Denmark. His father was Professor of Physiology at the University of Copenhagen. His mother was Ellen Adler from a Jewish banking family. Niels was brought up as a Lutheran but ostentatiously left the church in 1912 when getting married, which he did in a civil ceremony. A unique man, he was older than some of the other quantum theorists and had already won renown for his atomic model, which was the first attempt to express the workings of the atom in quantum terms. His institute in Copenhagen became the centre for young physicists such as Heisenberg, and it was in the lessons and extra-curricular discussions there that the Copenhagen Interpretation was worked out. This took place often in all-night discussions that reduced the participants to close to despair at the paradoxical reality they were uncovering. His biographer, Ruth Moore, writes:

“Both Bohr’s Institute for Theoretical Physics on the edge of a Copenhagen park and Aristotle’s Lyceum on the outskirts of Athens in a grove sacred to Apollo were centres to which the most able came and from which learning radiated. There were few schools like either in the twenty-three centuries that separated them.”5

In physical terms, Bohr and Heisenberg thrashed out the Copenhagen Model which expressed the concept of Complementarity of which the wave-particle is the most obvious example: wave and particle are two complementary aspects of something which we would be hard put to describe. This led Bohr to embody a similar attitude towards religion, which he and Heisenberg sometimes called ‘the old religions’. He did not entirely dismiss religion but assumed that they were complementary ways of talking about different aspects of reality. His dialectical opposite was Paul Dirac.

Dirac was the son of a Swiss immigrant who was a French teacher and an English mother. One biographer considered both father and son to have some degree of autism and that in the case of the latter it was actually helpful in his highly abstruse mathematical work. His work gave rise to the idea of anti-particles, e.g. the positron as the anti-particle of the electron. We will see later his trenchant statement of atheism and repudiation of religion as a young man.

Einstein was a German Jew whose philosophy was that of Spinoza, the Jewish philosopher who had been expelled from the Jewish community because of his startling ideas about God, revelation and the Bible. This is too complex an issue for us to do justice to, but suffice it to say that he did not believe in a ‘personal God’ i.e. One to Whom one prays and Whom one worships, and there is some sense in which he is regarded as believing that nature itself is the God to which he referred. That is perhaps too blunt and coarse a statement. Yet, all his life Einstein allowed people to assume that when he said ‘God’ or ‘the Lord’ he meant the same as others ordinarily do.

In one year, 1905, he published a number of papers on Special Relativity and other matters which mark the first articulation of the new physics after Planck’s groundbreaking discovery. Nevertheless, he would later become an intransigent opponent of much of quantum thinking , particularly the Uncertainty Principle, Complementarity and probabilistic interpretations, and he would work resolutely but unsuccessfully to restore determinism. He and Bohr had an ongoing exchange on this issue that spanned decades. Many modern physicists follow his lead in that endeavour.

Werner Heisenberg (1901 – 1976)

Heisenberg was raised as a Lutheran Christian. He had a lifelong interest in the philosophical tradition of Plato, Aristotle, Descartes and Kant, but was also deeply aware of Goethe’s work. He knew Heidegger, with whom he corresponded, and one of the most intriguing encounters must have been their meeting at the symposium in 1953 at which Heidegger presented “The Question Concerning Technology” and Heisenberg “The Picture of Nature in Modern Physics”. His wife Elizabeth is the sister of Fritz Schumacher, the author of Small is Beautiful.

Heisenberg later faced up to the reality that far from the bewildering plethora of sub-atomic particles being discovered in the large particle accelerators, they were being created as a result of the hugely intense energies of collision there through Einstein’s e=mc2. The cosmologists and sub-atomic particle theorists would reply that they are also being created in the most intense circumstances such as the centres of stars, black holes, quasars and in the initial ‘singularity’ known as the Big Bang. However that is, most of them have lives of fractions of nano-seconds.

He devoted many of his essays to reflections on philosophical themes and to the relationship between science and religion. We will see later some of his most interesting insights.

Pauli was descended on his father’s side from prominent Czech Jewish families who had converted to Roman Catholicism. His mother was a Roman Catholic daughter of a Catholic mother and Jewish father. Pauli grew up as a Catholic but eventually he and the family left the Church. He was considered to be a ‘deist’ i.e. someone who believed in the existence of God but not in prophets and revelation. He did not believe in a personal God. Later, after his mother’s suicide and a failed marriage to a dancer, on his father’s suggestion Pauli consulted Jung and underwent psychotherapy with one of Jung’s assistants and later with Jung himself with whom he continued to correspond and cooperate even after he had ceased therapy.

Schrödinger was an Austrian, son of a Catholic father and Lutheran mother. Schrödinger spent the years of the Second World War in Dublin at the Institute for Advanced Studies where he was to live for 17 years, becoming an Irish citizen. Alongside his undoubted achievements in quantum physics he is famous for his prescience in his book What is Life?هر in which he foresaw the discovery of genes. He considered himself an atheist but had a lifelong interest in Eastern religions and pantheism, the idea that everything is God in some way. He was also much influenced by Schopenhauer. In his Mind and Matter he wrote:

“The world is a construct of our sensations, perceptions, memories. It is convenient to regard it as existing objectively on its own.”6

This work is an extended meditation on the theme of reality being that of a single consciousness.

These are in fact only some of the main names in the new physics but there was a much wider circle of scientists who contributed in various ways.

Perhaps one of the most important aspects of these men, and one that is easy to overlook, is the manner in which they constituted a brotherhood of truth-seekers working together cooperatively to a common goal, something that would be shattered by the Second World War and done even more serious damage by the increasing commercialisation of science through the system of patents.

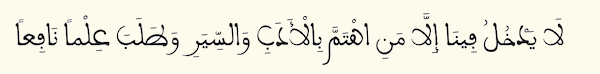

Inasmuch as scientists leave behind the very necessary rigour of their mathematical and experimental work and began to think aloud about its meanings, they enter a different domain and arguably tread on the ground of philosophy. Many are not equipped to think philosophically. Yet equally so, many philosophers are largely unable to follow scientists mathematical and scientific work and therefore unqualified to ground it in philosophy. Nevertheless, there is much to be said for Imām al-Ghazali’s observation that:

“…whoever takes up these mathematical sciences marvels at the fine precision of their details and the clarity of their proofs. Because of that, he forms a high opinion of the philosophers and assumes that all their sciences have the same lucidity and rational solidarity as this science of mathematics.”

This far-sighted perception is all too true of many of our subjects. They were absolutely gifted mathematically but it was not necessarily the case that they were equally clear thinkers in language and the concepts of philosophy and metaphysics. And yet Bohr to some extent, and Einstein and Heisenberg to a much larger extent worked hard to express themselves on a variety of issues in their essays.

Arguably the most significant of the 20th century philosophers, Martin Heidegger, recognised, however, that “the present leaders of atomic physics, Niels Bohr and [Werner] Heisenberg, think in a thoroughly philosophical way”.7

Apart from the clarity of thinking which a person brings to his work, there is of course also the issue of what he intends by it. Einstein’s advice to a young colleague who was considering an offer “to head up the world federalist movement nationally," was, "…if you’re a paid head of an organization nobody will pay any attention to what you say. If you want to influence the world, make a name for yourself in your own field, and then people will listen to you on other matters as well.” Since most science is done in youth and early manhood, almost all of our subjects went on to hold other positions and work on other issues, even when they remained in the fold of science.

Einstein held a position at Princeton but involved himself in a wide variety of matters throughout the rest of his life, including working for the state of Israel, at one point being offered the position of first president of Israel, which he declined. He also roundly condemned the Stern Gang for their atrocities and wrote to their fundraiser in the US “I am not willing to see anyone associated with those misled and criminal people.” He worked assiduously for the creation of a world state, which he regarded as the solution to the world’s many conflicts.

Bohr went on to try and work after the war for the sharing of the secrets of atomic energy, in which he was thwarted by Winston Churchill.

Heisenberg dedicated himself to what he had claimed was one of his reasons for staying in Germany throughout the war, which he was convinced the Nazis would lose, the restoration of German science and society.

Treating the New Physics from the perspective of religion is not entirely arbitrary, as I hope the many quotations here, and the recommended reading, show. The earnestness and selflessness with which many of them pursued the strange and paradoxical world their research unlocked is testament to their sincerity. They mark the transition in our culture from the Judaeo-Christian age to a post-Judaic, post-Christian age that has not yet found its way. Many of the figures were deists in that they believed in the Divine but not necessarily in Him as a personal God, or in revelation, prophets, acts of worship and the afterlife.

I would like to conclude with a passage from an essay by Heisenberg about a visit to Copenhagen in 1952 for a reunion with Niels Bohr, when during a walk Pauli unexpectedly asked him if he believed in a personal God. Heisenberg said:

“May I rephrase your question?” I asked. “I myself should prefer the following formulation: Can you, or anyone else, reach the central order of things or events, whose existence seems beyond doubt, as directly as you can reach the soul of another human being? I am using the term ‘soul’ quite deliberately so as not to be misunderstood. If you put your question like that, I would say yes. And because my own experiences do not matter so much, I might go on to remind you of Pascal’s famous text, the one he kept sewn in his jacket. It was headed ‘Fire’ and began with the words: ‘God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob - not of the philosophers and sages.”

[Pauli] “In other words, you think that you can become aware of the central order with the same intensity as of the soul of another person?”

[Heisenberg] “Perhaps.”

[Pauli] “Why did you use the word ‘soul’ and not simply speak of another person?”

[Heisenberg] “Precisely because the word ‘soul’ refers to the central order, to the inner core of a being whose outer manifestations may be highly diverse and pass our understanding.”8

That brings us to the end of today’s lecture. Recommended further reading includes my own article “Heisenberg’s Quantum Leap”, Heisenberg’s “Science and Religion” and his “Positivism, Metaphysics, and Religion”. The subject of our next lecture is The New Weapon and recommend preparatory reading is the book Heisenberg’s War by Thomas Powers, which is also useful for its very good exposition of the science which we have covered today. Thank you for your attention. Assalamu alaykum.

1 Werner Heisenberg, “Science and Religion”, Physics and Beyond. p.82

4 Das Wesen der Materie [The Nature of Matter], speech at Florence, Italy (1944) (from Archiv zur Geschichte der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, Abt. Va, Rep. 11 Planck, Nr. 1797)

5 Ruth Moore, Niels Bohr – the man, his science and the world they changed, p.4.

6 “Mind and Matter”, The Tarner Lectures, delivered at Trinity College, Cambridge in October 1956. What is Life. p.63

7 Heidegger, What is a Thing 1969: p.67

8Werner Heisenberg, ‘Positivism, Metaphysics, and Religion’, Physics and Beyond: Encounters and Conversations by Werner Heisenberg. Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc., 1971.