Review

All lectures are freely available on this site.

11. The Presence of the Divine in Literature

بسم الله الرحمن الرحيم وصلى الله على سيدنا محمد وعلى ءاله وصحبه أجمعين وسلّم

Title: The Presence of the Divine in Literature

Author: Shaykh Abdalhaqq Bewley

Publication date: 16th November 2013

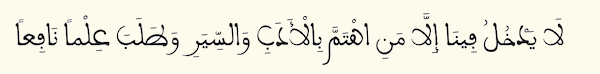

Assalamu alaykum. Welcome to the Civilisation and Society Programme of the MFAS. This is the eleventh of 12 sessions which make up the Society through Literature module. The lecture will last approximately 40 minutes during which time you should make a written note of any questions that may occur to you for clarification after the lecture.

“From the dark opening of the worn insides of the shoes the toilsome tread of the worker stands forth. In the stiffly solid heaviness of the shoes there is the accumulated tenacity of her slow trudge through the far-spreading and ever- uniform furrows of the field, swept by the raw wind. On the leather there lies the dampness and saturation of the soil. Under the soles there slides the loneliness of the field path as the evening declines. In the shoes there vibrates the silent call of the earth, its quiet gift of the ripening corn and its enigmatic self-refusal in the fallow desolation of the wintry field. This equipment is pervaded by uncomplaining anxiety about the certainty of bread, the wordless joy of having once more withstood want, the trembling before the advent of birth and shivering at the surrounding menace of death. This equipment belongs to the earth and it is protected in the world of the peasant woman. From out of this protected belonging the equipment itself arises to its resting-in-self.”

This is Martin Heidegger’s beautiful description of Van Gogh’s famous painting of an old pair of boots. The reason I have started this talk about the presence of the Divine in literature with it, is that it stems directly from Heidegger’s great insight that a work of art is what it is because it discloses the truth of its subject, because it shows a thing to be what it really is, because it reveals the true essence of its subject. Prior to giving that eloquent description, Heidegger says: “There is nothing surrounding this pair of peasant shoes in or to which they might belong, only an undefined space. There are not even clods from the soil of the field or the path through it sticking to them, which might at least hint at their employment. A pair of peasant shoes and nothing more. And yet.” This final phrase “And yet.” opens the way to the sublime interpretation of the painting that I began with. The key to this paradox – the stark simplicity of the object portrayed and the extraordinarily rich impression they convey to the person who sees the painting – lies in Heidegger’s penultimate sentence: “This equipment belongs to the earth and it is protected in the world of the peasant woman.”

In this sentence the words “earth” and “world” are italicized in order to emphasise the idiosyncratic way that Heidegger is using these two terms. The word “earth” in his usage of it really signifies the outward form of a thing, such as might be captured in a simple snapshot of an object. The word “world” encompasses the meaning of the thing, its passage through time, its complete context. In a true work of art the artist both captures the form and also conveys the meaning of his subject, thereby in a real sense bringing it to life, and more than that somehow conveying its true essence. Art is a crossroads where earth and world share a symbiotic relationship. He says about this: “When artworks disclose entities, they bring the meeting of earth and world to our attention.” And speaking of works of art he says; “The setting-into-work of truth thrusts up the awesome and at the same time thrusts down the ordinary.”

By bringing together form and meaning in this truthful way, the artist somehow transcends the ordinariness, the day-to-dayness, the earthliness, of the subject being addressed and gives it a kind of relevance and universality that escapes the limitations of the time and place in which the artwork is produced. It means that every true work of art partakes of the Real and so, from one point of view, can be said to have a connection with the Divine. This is demonstrated by the living quality possessed by true works of art through which they are indeed connected to the Divine Name al-Hayy, the Living, and by the fact that such works survive through time, whereas so many thousands of others do not, thereby connecting them to the Divine Name al-Baqi, the Ever-Continuing. Heidegger takes as examples the painting referred to, a Greek temple, and the poetry of Holderlin, but, of course, the principle applies to artistic endeavours of all kinds whether music, painting, sculpture, literature or drama. The point I am making is that, as a work of art, there is a certain aspect of the Divine presence manifest in every true work of literature, even though the author may not necessarily acknowledge this to be the case, and may even in some cases deny it completely.

Having made this general point I want to say that my purpose in this talk is, however, to see the way that certain writers have, as it were, had a head to head encounter with the Divine in what they have written. This has been necessarily dealt with by me in a rather arbitrary manner, restricted by my own reading and the time at our disposal. There are myriads of other ways it might have been approached and thousands of authors who have had much to say on this subject. I would particularly like to mention that I have concentrated almost exclusively on the European tradition and have, therefore, neglected the classical authors and the rich Islamic tradition, which, of course, is overflowing with exposition of this matter from every angle. My limited objective here is, by taking excerpts from the writings of a few authors I have read, to look at how the impoverished spiritual landscape of our own time was expressed by some of them, how the possibility of spirituality is broached by others and, finally, how undisguised belief in the Divine shines through in yet others. By allowing the authors, as much as possible, to speak for themselves, what results is a literary journey from darkness into light.

I start with two works that eloquently, in very different ways, sum up the desolation of the spiritual landscape of the age in which we live. The first is Matthew Arnolds celebrated poem:

The sea is calm to-night.

The tide is full, the moon lies fair

Upon the straits; on the French coast the light

Gleams and is gone; the cliffs of England stand,

Glimmering and vast, out in the tranquil bay.

Come to the window, sweet is the night-air!

Only, from the long line of spray

Where the sea meets the moon-blanch'd land,

Listen! you hear the grating roar

Of pebbles which the waves draw back, and fling,

At their return, up the high strand,

Begin, and cease, and then again begin,

With tremulous cadence slow, and bring

The eternal note of sadness in.

Sophocles long ago

Heard it on the Aegean, and it brought

Into his mind the turbid ebb and flow

Of human misery; we

Find also in the sound a thought,

Hearing it by this distant northern sea.

The Sea of Faith

Was once, too, at the full, and round earth's shore

Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furl'd.

But now I only hear

Its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar,

Retreating, to the breath

Of the night-wind, down the vast edges drear

And naked shingles of the world.

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

The second is an extract from the first chapter of Book III of Thomas Carlyle’s

But, it is said, our religion is gone: we no longer believe in St. Edmund, no longer see the figure of him 'on the rim of the sky,' minatory or confirmatory! God's absolute Laws, sanctioned by an eternal Heaven and an eternal Hell, have become Moral Philosophies, sanctioned by able computations of Profit and Loss, by weak considerations of Pleasures of Virtue and the Moral Sublime.

It is even so. To speak in the ancient dialect, we 'have forgotten God;' in the most modern dialect and very truth of the matter, we have taken up the Fact of this Universe as it is not. We have quietly closed our eyes to the eternal Substance of things, and opened them only to the Shews and Shams of things. We quietly believe this Universe to be intrinsically a great unintelligible PERHAPS; extrinsically, clear enough, it is a great, most extensive Cattlefold and Workhouse, with most extensive Kitchen- ranges, Dining-tables, whereat he is wise who can find a place! All the Truth of this Universe is uncertain; only the profit and loss of it, the pudding and praise of it, are and remain very visible to the practical man.

There is no longer any God for us! God's Laws are become a Greatest- Happiness Principle, a Parliamentary Expediency: the Heavens overarch us only as an Astronomical Time-keeper; a butt for Herschel-telescopes to shoot science at, to shoot sentimentalities at: in our and old Jonson's dialect, man has lost the soul out of him; and now, after the due period, begins to find the want of it! This is verily the plague-spot; centre of the universal Social Gangrene, threatening all modern things with frightful death. To him that will consider it, here is the stem, with its roots and taproot, with its world-wide upas-boughs and accursed poison- exudations, under which the world lies writhing in atrophy and agony. You touch the focal-centre of all our disease, of our frightful nosology of diseases, when you lay your hand on this. There is no religion; there is no God; man has lost his soul, and vainly seeks antiseptic salt. Vainly: in killing Kings, in passing Reform Bills, in French Revolutions, Manchester Insurrections, is found no remedy. The foul elephantine leprosy, alleviated for an hour, reappears in new force and desperateness next hour.

Next, as an expression of this view of the bankruptcy of human spirituality in our age I will read two passages from E.M. Forster’s novel A Passage to India. The first is part of a conversation between two of the major characters in the book, Mrs Moore and her son, a government official in British India. She has come from England to visit him in India. The second extract is about an experience Mrs Moore has later during that visit.

He said, “We’re not pleasant in India, and we don’t intend to be pleasant. We’ve something more important to do.”

“I’m going to argue, and indeed dictate,” she said clinking her rings. “The English are out here to be pleasant.”

“How do you make that out, mother?” he asked, speaking gently again, for he was ashamed of his irritability.

“Because India is part of the earth and God has put us on the earth to be pleasant to each other. God . . . is . . . love.” She hesitated seeing how much he disliked the argument, but something made her go on. “God has put us on earth to love our neighbours and to show it, and He is omnipresent, even in India, to see how we are succeeding.” He looked gloomy, and a little anxious. He knew this religious strain in her, and that it was a symptom of bad health; there had been much of it when his stepfather died. He thought, “She is certainly ageing, and I ought not to be vexed with anything she says.”

“The desire to behave pleasantly satisfies God, “ she continued. “The sincere if impotent desire wins His blessing. I think everyone fails, but there are so many kinds of failure. Good will and more good will and more good will. Though I speak with the tongues of ...”

He waited until she had done, and then said gently, “I quite see that. I suppose I ought to get off to my files now, and you’ll be going to bed.”

"I suppose so, I suppose so." They did not part for a few minutes, but the conversation had become unreal since Christianity had entered it. Ronny approved of religion as long as it endorsed the National Anthem, but he objected when it attempted to influence his life. Then he would say, in respectful yet decided tones, “I don't think it does to talk about these things, every fellow has to work out his own religion,” and any fellow who heard him muttered, “Hear! Hear!”

Mrs. Moore felt that she had made a mistake in mentioning God, but she found him increasingly difficult to avoid as she grew older, and he had been constantly in her thoughts since she entered India, though oddly enough he satisfied her less. She must needs pronounce his name frequently, as the greatest she knew, yet she had never found it less efficacious. Outside the arch there seemed always an arch, beyond the remotest echo a silence.

A Marabar cave had been horrid as far as Mrs Moore was concerned, for she had nearly fainted in it, and had some difficulty in preventing herself from saying so as soon as she got into the air again. There was also a terrifying echo. The echo in a Marabar cave is entirely devoid of distinction. Whatever is said, the same monotonous noise replies, and quivers up and down the walls until it is absorbed into the roof. "Bourn" is the sound as far as the human alphabet can express it, or "bou-ourn," or "ou-boum," utterly dull. Hope, politeness, the blowing of a nose, the squeak of a boot, all produce "bourn."

Nothing evil had been in the cave, but she had not enjoyed herself; no, she had not enjoyed herself. ... The more she thought over it, the more disagreeable and frightening it became. She minded it much more now than at the time. The crush and the smells she could forget, but the echo began in some indescribable way to undermine her hold on life. Coming at a moment when she chanced to be fatigued, it had managed to murmur, "Pathos, piety, courage—they exist, but are identical, and so is filth. Everything exists, nothing has value." If one had spoken vileness in that place, or quoted lofty poetry, the comment would have been the same--" ou-bourn." ... Devils are of the North, and poems can be written about them, but no one could romanticize the Marabar because it robbed infinity and eternity of their vastness, the only quality that accommodates them to mankind.

She tried to go on with her letter, reminding herself that she was only an elderly woman who had got up too early in the morning and journeyed too far, that the despair creeping over her was merely her despair, her personal weakness, and that even if she got a sunstroke and went mad the rest of the world would go on. But suddenly, at the edge of her mind. Religion appeared, poor little talkative Christianity, and she knew that all its divine words from "Let there be Light" to "It is finished" only amounted to "bourn." Then she was terrified over an area larger than usual; the universe, never comprehensible to her intellect, offered no repose to her soul, the mood of the last two months took definite form at last, and she realized that she didn't want to write to her children, didn't want to communicate with anyone, not even with God.

Next I want to read a poem by Thomas Hardy called The Darkling Thrush. In it, as in almost all of his novels, he paints a very dismal picture of the world around him and yet, as you will hear, he ends by opening up a way to a quite different view of existence.

I leant upon a coppice gate

When Frost was spectre-grey,

And Winter's dregs made desolate

The weakening eye of day.

The tangled bine-stems scored the sky

Like strings of broken lyres,

And all mankind that haunted nigh

Had sought their household fires.

The land's sharp features seemed to be

The Century's corpse outleant,

His crypt the cloudy canopy,

The wind his death-lament.

The ancient pulse of germ and birth

Was shrunken hard and dry,

And every spirit upon earth

Seemed fervourless as I.

At once a voice arose among

The bleak twigs overhead

In a full-hearted evensong

Of joy illimited;

An aged thrush, frail, gaunt, and small,

In blast-beruffled plume,

Had chosen thus to fling his soul

Upon the growing gloom.

So little cause for carolings

Of such ecstatic sound

Was written on terrestrial things

Afar or nigh around,

That I could think there trembled through

His happy good-night air

Some blessed Hope, whereof he knew

And I was unaware.

And now a look at the tussle between faith and denial, between belief and unbelief. It might be said that this is the central theme of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s final great novel The Brothers Karamazov. The first extract from it I will read is part of a conversation between two of the brothers, Ivan – the sceptic intellectual – and Alyosha – the ingenuous believer – and a third character Fyodor Pavlovich, who, in this instance, is acting as a foil for them. Fyodor Pavlovich says:

“Alyosha, do you believe that I’m nothing but a buffoon?”

“No, I don’t believe it.”

“And I believe you don’t, and that you speak the truth. You look sincere and you speak sincerely. But not Ivan. Ivan’s supercilious.... I’d make an end of your monks, though, all the same. I’d take all that mystic stuff and suppress it, once for all, all over Russia, so as to bring all the fools to reason. And the gold and the silver that would flow into the mint!”

“But why suppress it?” asked Ivan. “That Truth may prevail. That’s why.”

“Well, if Truth were to prevail, you know, you’d be the first to be robbed and suppressed.”

“Ah! I dare say you’re right. Ah, I’m an ass!” burst out Fyodor Pavlovitch, striking himself lightly on the forehead. “Well, your monastery may stand then, Alyosha, if that’s how it is. And we clever people will sit snug and enjoy our brandy. You know, Ivan, it must have been so ordained by the Almighty Himself. Ivan, speak, is there a God or not? Stay, speak the truth, speak seriously. Why are you laughing again?”

“I’m laughing that you should have made a clever remark just now about Smerdyakov’s belief in the existence of two saints who could move mountains.”

“Why, am I like him now, then?”

“Very much.”

“Well, that shows I’m a Russian, too, and I have a Russian characteristic. And you may be caught in the same way, though you are a philosopher. Shall I catch you? What do you bet that I’ll catch you to-morrow. Speak, all the same, is there a God, or not? Only, be serious. I want you to be serious now.”

“No, there is no God.”

“Alyosha, is there a God?”

“There is.”

“Ivan, and is there immortality of some sort, just a little, just a tiny bit?”

“There is no immortality either.”

“None at all?”

“None at all.”

“There’s absolute nothingness then. Perhaps there is just something? Anything is better than nothing!”

“Absolute nothingness.”

“Alyosha, is there immortality?”

“There is.”

“God and immortality?”

“God and immortality. In God is immortality.”

“H’m! It’s more likely Ivan’s right. Good Lord! to think what faith, what force of all kinds, man has lavished for nothing, on that dream, and for how many thousand years. Who is it laughing at man? Ivan! For the last time, once for all, is there a God or not? I ask for the last time!”

“And for the last time there is not.”

And yet on the tongue of another character in the novel, the venerable hermit Zosima, Dostoevski speaks in quite another tone and shows a sincere openness to the possibility of belief in the Divine.

“Fear nothing and never be afraid; and don’t fret. If only your penitence fail not, God will forgive all. There is no sin, and there can be no sin on all the earth, which the Lord will not forgive to the truly repentant! Man cannot commit a sin so great as to exhaust the infinite love of God. Can there be a sin which could exceed the love of God? Think only of repentance, continual repentance, but dismiss fear altogether. Believe that God loves you as you cannot conceive; that He loves you with your sin, in your sin. It has been said of old that over one repentant sinner there is more joy in heaven than over ten righteous men. Go, and fear not. If you are penitent, you love. And if you love you are of God. All things are atoned for, all things are saved by love. If I, a sinner, even as you are, am tender with you and have pity on you, how much more will God. Love is such a priceless treasure that you can redeem the whole world by it, and expiate not only your own sins but the sins of others.”

And again in an exchange between the hermit and one of the female characters in the novel, the woman says:

“I say to myself, ‘What if I’ve been believing all my life, and when I come to die there’s nothing but the burdocks growing on my grave?’ as I read in some author. It’s awful! How—how can I get back my faith? But I only believed when I was a little child, mechanically, without thinking of anything. How, how is one to prove it? I have come now to lay my soul before you and to ask you about it. If I let this chance slip, no one all my life will answer me. How can I prove it? How can I convince myself? Oh, how unhappy I am! I stand and look about me and see that scarcely any one else cares; no one troubles his head about it, and I’m the only one who can’t stand it. It’s deadly—deadly!”

The hermit replies, “No doubt. But there’s no proving it, though you can be convinced of it.”

“How?”

“By the experience of active love. Strive to love your neighbor actively and indefatigably. In as far as you advance in love you will grow surer of the reality of God and of the immortality of your soul. If you attain to perfect self-forgetfulness in the love of your neighbor, then you will believe without doubt, and no doubt can possibly enter your soul. This has been tried. This is certain.”

From this possibility of faith in the Divine expressed by Dostoevsky we move on to three writers in whom that faith is firmly established: George Herbert, Gerard Manley Hopkins and D.H. Lawrence. The first example is a sonnet, in which Herbert talks of the relationship between literature and the Divine and the second is Hopkins’ famous poem Pied Beauty, a staple of many collections of verse for young people, which is none the less beautiful for all that.

My God, where is that ancient heat towards thee,

Wherewith whole showls of Martyrs once did burn,

Besides their other flames? Doth Poetry

Wear Venus livery? only serve her turn?

Why are not Sonnets made of thee? and layes

Upon thine Altar burnt? Cannot thy love

Heighten a spirit to sound out thy praise

As well as any she? Cannot thy Dove

Out-strip their Cupid easily in flight?

Or, since thy wayes are deep, and still the fame,

Will not a verse run smooth that bears thy name!

Why doth that fire, which by thy power and might

Each breast does feel, no braver fuel choose

Than that, which one day, Worms, may chance refuse?

Glory be to God for dappled things —

For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow;

For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim;

Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls; finches' wings;

Landscape plotted and pieced — fold, fallow, and plough;

And áll trádes, their gear and tackle and trim.

All things counter, original, spare, strange;

Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?)

With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim;

He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change:

Praise Him.

Next we have a passage from Kangaroo, one of D.H. Lawrence’s lesser-known novels. In it Lawrence clearly enunciates his clear belief in the Divine Reality, in his own idiosyncratic and personal way it is true, but with absolute unambiguity.

But now, for the moment he felt he had cut himself clear. He was exhausted and almost wrecked – but he felt clear again. If no other ghastly arm of the octopus should flash out and encircle him.

For the moment he felt himself lying inert, but clear, the dragon dead. The ever-renewed dragon of a great old ideal, with its foul poison- breath. It seemed, as if, for himself, he had killed it. That was now all he wanted: to get clear. Not to save humanity or to help humanity or to have anything to do with humanity. No – no. Kangaroo had been his last embrace with humanity. Now, all he wanted was to cut himself clear. To be clear of humanity altogether, to be alone. To be clear of love, and pity, and hate. To be alone from it all. To cut himself finally clear from the last encircling arm of the octopus humanity. To turn to the old dark gods, who had waited so long in the outer dark.

Humanity could do as it liked: he did not care. So long as he could get his own soul clear. For he believed in the inward soul, in the profound unconscious of man. Not an ideal God. The ideal God is a proposition of the mental consciousness, all-too-limitedly human. “No,” he said to himself. “There IS God. But forever dark, forever unrealisable: forever and forever. The unutterable name, because it can never have a name. The great living darkness which we represent by the glyph, God.” There is this ever-present, living darkness inexhaustible and unknowable. It IS. And it is all the God and the gods.

And every LIVING human soul is a well-head to this darkness of the living unutterable. Into every living soul wells up the darkness, the unutterable. And then there is travail of the visible with the invisible. Man is in travail with his own soul, while ever his soul lives. Into his unconscious surges a new flood of the God-darkness, the living unutterable. And this unutterable is like a germ, a foetus with which he must travail, bringing it at last into utterance, into action, into BEING.

But in most people the soul is withered at the source, like a woman whose ovaries withered before she became a woman, or a man whose sex-glands died at the moment when they should have come into life. Like unsexed people, the mass of mankind is soulless. Because to persist in resistance of the sensitive influx of the dark gradually withers the soul, makes it die, and leaves a human idealist and an automaton. Most people are dead, and scurrying and talking in the sleep of death. Life has its automatic side, sometimes in direct conflict with the spontaneous soul. Then there is a fight. And the spontaneous soul must extricate itself from the meshes of the ALMOST automatic white octopus of the human ideal, the octopus of humanity. It must struggle clear, knowing what it is doing: not waste itself in revenge. The revenge is inevitable enough, for each denial of the spontaneous dark soul creates the reflex of its own revenge. But the greatest revenge on the lie is to get clear of the lie.

The long travail. The long gestation of the soul within a man, and the final parturition, the birth of a new way of knowing, a new God- influx. A new idea, true enough. But at the centre, the old anti-idea: the dark, the unutterable God. This time not a God scribbling on tablets of stone or bronze. No everlasting decalogues. No sermons on mounts, either. The dark God, the forever unrevealed. The God who is many gods to many men: all things to all men.

Finally I would like to read two more poems from Gerard Manley Hopkins and George Herbert. In the first, in his unique and inimitable style, Hopkins uses the sonnet form to declare his faith in the face of modern blindness to the Divine Presence. The second is Herbert’s poem the Elixir. I first knew this in my childhood as a hymn. It gave me spiritual nourishment then and later and has remained with me as a source of inspiration throughout my life.

THE WORLD is charged with the grandeur of God.

It will flame out, like shining from shook foil;

It gathers to a greatness, like the ooze of oil

Crushed. Why do men then now not reck his rod?

Generations have trod, have trod, have trod;

And all is seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil;

And wears man’s smudge and shares man’s smell: the soil

Is bare now, nor can foot feel, being shod.

And for all this, nature is never spent;

There lives the dearest freshness deep down things;

And though the last lights off the black West went

Oh, morning, at the brown brink eastward, springs –

Because the Holy Ghost over the bent

World broods with warm breast and with ah! bright wings.

Teach me, my God and King,

In all things Thee to see,

And what I do in anything

To do it as for Thee.

A man that looks on glass,

On it may stay his eye;

Or it he pleaseth, through it pass,

And then the heav'n espy.

All may of Thee partake:

Nothing can be so mean,

Which with his tincture--"for Thy sake"--

Will not grow bright and clean.

A servant with this clause

Makes drudgery divine:

Who sweeps a room as for Thy laws,

Makes that and th' action fine.

This is the famous stone

That turneth all to gold;

For that which God doth touch and own

Cannot for less be told.

I will leave the last word to the Divine Itself, to the word of God as revealed in the Qur’an.

Allah

There is no god but Him,

the Living, the Self-Sustaining.

He is not subject to drowsiness or sleep.

Everything in the heavens and the earth belongs to Him.

Who can intercede with Him except by His permission?

He knows what is before them and what is behind them

but they cannot grasp any of His knowledge save what He wills.

His Footstool encompasses the heavens and the earth

and their preservation does not tire Him.

He is the Most High, the Magnificent.

Say: He is Allah,

Absolute Oneness,

Allah, the Everlasting Sustainer of all.

He has not given birth and was not born.

And no one is comparable to Him.

That brings us to the end of today’s lecture. Thank you for your attention. Assalamu alaykum.